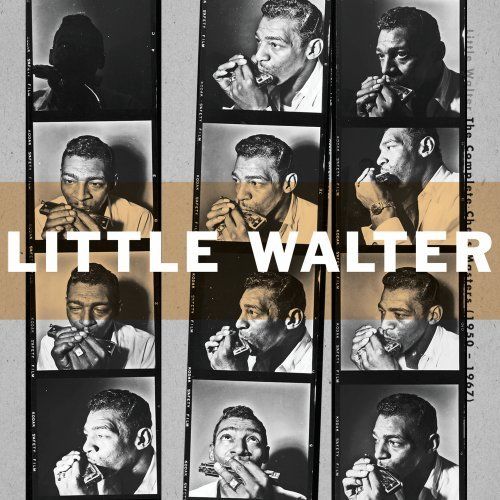

On the 1st of May 1930, in the depths of Louisiana, Marion Walter Jacobs was born. Thus began the tumultuous journey of the boy who would go on to become a musical visionary known as Little Walter.

Walter was raised in Rapides Parish, Louisiana, where he taught himself to play the harmonica. By the age of 12 he had quit school and left rural Louisiana to travel, working odd jobs on the road, and busking across America.

The young student of the blues honed his skills on the harmonica and guitar by performing with his elders. Bluesmen including Sonny Boy Williamson II, Sunnyland Slim, and Honeyboy Edwards, all helped Walter better himself before he journeyed to Chicago in 1945.

Upon arriving in the Windy City, Walter found sporadic work as a guitarist with Chicago blues players such as Floyd Jones, but it was his impressively advanced harmonica playing that was gaining attention.

Walter was already well on his way to becoming a full-fledged musical mastermind, and would soon make some crucial changes to the way harmonica was played.

Tired of having electric guitars blocking the sounds of his harmonica Walter began cupping a small microphone in his hands along with the harmonica, and plugging the microphone into a guitar amp. This strategy helped him compete with the guitars’ resonance.

While this technique was already being used by fellow harmonica players, Walter took things a step further. Unlike his harp blowing counterparts, he began pushing his amplifiers to the extreme — using them far beyond their intended technical limits allowed him to explore innovative tones and sound effects.

Walter was the first musician of any kind to use electronic distortion, and he was fast becoming one of Chicago blues’ most conspicuous characters.

Walter joined forces with Muddy Waters’ band in 1948, and by 1950 he was playing acoustic harmonica on Mud’s recordings for Chess Records. The very first recording of Walter’s amplified harmonica was on Waters’ “Country Boy,” recorded in 1951.

Although he left Waters’ band in ’52, Chess persisted in hiring Walter to play harp on Waters’ studio tracks. As a result, he features on the majority of Waters’ classic recordings from the 1950s.

Alongside his harmonica playing, Walter played guitar on a few early Chess sessions with Waters and Jimmy Rogers. He also played with Memphis Minnie, Johnny Shines, Floyd Jones, Bo Diddley, Otis Rush, Johnny Young, and Robert Nighthawk, among many others.

After many years as a sideman, Walter stepped into the limelight and became his own bandleader for Chess’s subsidiary label, Checker Records in 1952. The first take of the first song he recorded at his initial recording session, “Juke,” became his inaugural hit, spending eight weeks at number-one on the Billboard R&B chart.

The song remains the only harmonica instrumental ever to hit number one on Billboard. To this day “Juke” is the most successful track of any artist on the Chess label. Walter had fourteen top-ten hits on the Billboard R&B charts between ’52 and ’58, including two number one hits, the later hit being “My Babe” in 1955.

Walter’s sound was ahead of its time and more up-tempo than what the rest of the Chicago blues had to offer at the time. As a harmonica player he was rhythmically freer, and a lot less unvarying than most blues harpists of his time. Little Walter stood out and made his way to the top, yet his musical triumphs couldn’t save him from himself.

Despite his successes, Walter was an alcoholic who lived life to the maximum. Known for being hot-headed and quick-tempered, Walter was a regular brawler. He was subjected to numerous beatings throughout his life, leaving his face and body bruised, battered, and scarred. Walter continually pushed his body to its limit, which ultimately resulted in his premature death at 37.

The greatest harmonica player to ever blow the blues died in his sleep on February 15th, 1968, following a bar fight in the South Side of Chicago. The exact circumstances surrounding his death remain a mystery.

While some claim that his death was the result of a blow to the head from the brother of one of Walter’s many female companions, others dispute this, saying that he was smacked across the head with a pipe over a bad gambling debt.

According to the official death certificate, Walter’s cause of death was coronary thrombosis. He suffered such insignificant external injuries that police reported the cause as “unknown or natural causes.” It’s been said that the aggressor in Walter’s final fight could have aggravated the damage he had sustained in previous altercations, leading to the fatality.

Walter’s longtime musical companion, Muddy Waters, wasn’t surprised by news of his friend’s death, saying “Little Walter was dead ten years before he died.”

The untamed bad boy of the blues was laid to rest at St. Mary’s Cemetery, in Evergreen Park, Illinois. His grave remained unmarked until 1991 when two fans had a marker designed, and put in place.

It was a tragic, and wildly underwhelming end to a life that had been filled with chaos and color, and bought so much innovation to the world of harmonica.

Little Walter was among the first class of inductees into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1980. In 2008, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and won a Grammy® Hall of Fame award for “Juke.”